Dr. Hans Zellweger was a tall, adventuresome doctor from a patrician family in Chur, the oldest town in Switzerland. After seeing the devastating effects of polio after World War I, his life goal was to understand neuromuscular disorders in children. After training across Europe, and working with Dr. Albett Schweitzer in Africa, he became chief resident at the children’s hospital in Zurich, the Kinderspital. He published a paper in 1946 where he noted that sometime the floppy babies also had hormone problems, and he identified one that became very fat at a young age and in retrospect probably had Prader-Willi syndrome. But his other case was thin. Dr. Zellweger had come close, but he had not yet zeroed in on PWS.

When Zellweger left Zurich for Beirut in 1951, Andrea Prader, another Swiss pediatrician, became the new chief resident at Kinderspital. He was ten years younger than Zellweger and had been trained by him in pediatrics. Prader picked up Zellweger’s floppy baby project and spotted a unique pattern in a patient named Albert, whom he had first seen with Zellweger: floppy at birth, underdeveloped genitals, fat by around two years old, short, small hands and feet, and intellectually disabled.

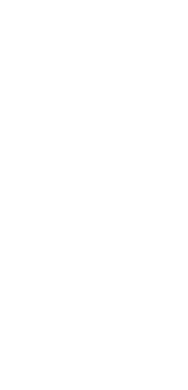

Prader, in collaboration with Heinrich Willi, the head of the newborn nursery, and Alexis Labhart, an endocrinologist in private practice, identified 8 other cases, all younger than Albert. They published their paper in 1956, with Prader as the first author. The syndrome was initially called Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome (PLWS) and the name changed to Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS). Though Labhart was eventually dropped from the name of the syndrome, Prader always insisted on recognizing Labhart’s role.

Discovering the syndrome was a huge achievement, but it was not recognized as such at the time. The paper was published in a small Swiss journal, in German. In the 1960s, other doctors began to investigate, but they still didn’t know what caused the obesity. The majority view was simply that they were eating too much.

After eight years in Beirut, Zellweger moved to the University of Iowa in 1959. He began diagnosing PWS in his patients and by the late 1960s, he had 14 cases. He noted they had “deficient control of their emotions. They show exuberant feelings of joy and pleasure…they can also be extremely stubborn.”

It was not until 1972 that a review of PWS was published in The Journal of Pediatrics, a publication widely read by pediatricians. As recently as 60 to 70 years ago, many families did not know what to do with children like these and a common solution was to give them up to be raised by an institution. Even in the 1970s, the medical literature had nothing good in it for families of children with this syndrome.

Dr. Andrea Prader came to the United States in 1984 to attend the PWSA | USA conference in Minneapolis, MN. He visited the residents at Oakwood and was impressed by the conference and PWSA | USA. He said, “You were the first Prader-Willi syndrome association in the world bringing together parents, doctors, other health workers and teachers. It is one of the most admirable qualities of American people, to develop very powerful private initiative; to have a strong will to help each other; not to be ashamed to have a so-called abnormal child and to go public in support of these children.” The International Organisation of Prader-Willi Syndrome (IPWSO) would not be formed for another 30 years, and was formed by the scientific community, unlike PWSA | USA’s early parents.

Hans Zellweger died in 1990 at the age of 80. He took his own life. Zellweger, who had shown so much compassion and understanding for people with PWS and their families held himself to a harsher standard.

Andrea Prader died in 2001 at the age of 81. Like Zellweger, his final years were not easy. After losing his wife of nearly 50 years in 1995, he lost his zest and curiosity for science. But despite the sad ending, he had accomplished what he set out to do in life: make scientific discoveries. Besides discovering Prader-Willi syndrome, he discovered several inborn errors of metabolism and became a worldwide leader in the study of growth and puberty.

Alexis Labhart died in 1994 at the age of 78. Heinrich Willi died in 1971 at the age of 71.

Contributed by Julie Doherty

Perry A. Zirkel has written more than 1,500 publications on various aspects of school law, with an emphasis on legal issues in special education. He writes a regular column for NAESP’s Principal magazine and NASP’s Communiqué newsletter, and he did so previously for Phi Delta Kappan and Teaching Exceptional Children.

Perry A. Zirkel has written more than 1,500 publications on various aspects of school law, with an emphasis on legal issues in special education. He writes a regular column for NAESP’s Principal magazine and NASP’s Communiqué newsletter, and he did so previously for Phi Delta Kappan and Teaching Exceptional Children. Jennifer Bolander has been serving as a Special Education Specialist for PWSA (USA) since October of 2015. She is a graduate of John Carroll University and lives in Ohio with her husband Brad and daughters Kate (17), and Sophia (13) who was born with PWS.

Jennifer Bolander has been serving as a Special Education Specialist for PWSA (USA) since October of 2015. She is a graduate of John Carroll University and lives in Ohio with her husband Brad and daughters Kate (17), and Sophia (13) who was born with PWS. Dr. Amy McTighe is the PWS Program Manager and Inpatient Teacher at the Center for Prader-Willi Syndrome at the Children’s Institute of Pittsburgh. She graduated from Duquesne University receiving her Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Education with a focus on elementary education, special education, and language arts.

Dr. Amy McTighe is the PWS Program Manager and Inpatient Teacher at the Center for Prader-Willi Syndrome at the Children’s Institute of Pittsburgh. She graduated from Duquesne University receiving her Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Education with a focus on elementary education, special education, and language arts. Evan has worked with the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association (USA) since 2007 primarily as a Crisis Intervention and Family Support Counselor. Evans works with parents and schools to foster strong collaborative relationships and appropriate educational environments for students with PWS.

Evan has worked with the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association (USA) since 2007 primarily as a Crisis Intervention and Family Support Counselor. Evans works with parents and schools to foster strong collaborative relationships and appropriate educational environments for students with PWS. Staci Zimmerman works for Prader-Willi Syndrome Association of Colorado as an Individualized Education Program (IEP) consultant. Staci collaborates with the PWS multi-disciplinary clinic at the Children’s Hospital in Denver supporting families and school districts around the United States with their child’s Individual Educational Plan.

Staci Zimmerman works for Prader-Willi Syndrome Association of Colorado as an Individualized Education Program (IEP) consultant. Staci collaborates with the PWS multi-disciplinary clinic at the Children’s Hospital in Denver supporting families and school districts around the United States with their child’s Individual Educational Plan. Founded in 2001, SDLC is a non-profit legal services organization dedicated to protecting and advancing the legal rights of people with disabilities throughout the South. It partners with the Southern Poverty Law Center, Protection and Advocacy (P&A) programs, Legal Services Corporations (LSC) and disability organizations on major, systemic disability rights issues involving the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and the federal Medicaid Act. Recently in November 2014, Jim retired.

Founded in 2001, SDLC is a non-profit legal services organization dedicated to protecting and advancing the legal rights of people with disabilities throughout the South. It partners with the Southern Poverty Law Center, Protection and Advocacy (P&A) programs, Legal Services Corporations (LSC) and disability organizations on major, systemic disability rights issues involving the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and the federal Medicaid Act. Recently in November 2014, Jim retired.