Steph and Waylon Krumvieda, Grand Forks, N.D., experienced a different leap into parenthood.

Although her due date was Christmas Eve, Sophie Kate Krumvieda, was born Jan. 3, 2017.

“She sounded like a little kitten. She didn’t really cry, just a little meow, literally so soft and quiet,” Steph recalls.

Weighing 5 pounds, 10 ounces and measuring 20 inches long, Sophie was tremendously weak.

“The doctors chalked it up to me being overdue and sick during my pregnancy,” Steph says.

After routine newborn testing, the doctors knew something wasn’t quite right. Sophie continued to defy every expectation of a newborn. When taken to the nursery, Sophie refused to eat and was later admitted to the NICU.

At two days old, the infant received a feeding tube in her nose. The doctors performed many tests to diagnose what was wrong with the tiny, fragile girl. After several blood tests, Sophie was transferred to Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

About the time Sophie was loaded into the 400-pound incubator cart, complete with oxygen tanks and other equipment needed to transport her nearly 400 miles, doctors finally solved the mystery thanks to a genetic test performed a week prior.

“It was very intimidating to see your tiny, fragile daughter in this big box,” Steph says. “I remember the three words: Prader-Willi Syndrome.”

Prader-Willi Syndrome defined

Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) was discovered by two doctors, Andrea Prader and Heinrich Willi, in the 1950s.

Kathy Clark, a nurse practitioner and coordinator of medical affairs for the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association, says the disorder is caused by abnormal chromosomes. In the case of people with PWS, the tiniest mistake in the chromosome can mean a drastic change for the individual. Chromosome 15 is to blame.

“It is important to have the father’s chromosome 15 region,” Clark says. “If it’s not available, then it renders the individual missing some very important information. It’s not that the father gave the child a bad chromosome — it’s that the region somehow went awry at the time of conception.”

At the moment of conception, the chromosomes link up. Each female chromosome links with the correlating male chromosome — one by one — until all 23 chromosomes have found their partner. In Sophie’s case, however, her father’s side of chromosome 15 missed its place in the lineup.

“They described it as a pause,” Waylon says. “There was a pause for just a brief moment, and it missed a portion of (my wife’s) chromosome.”

When a baby with PWS is born — often earlier than the standard 40 weeks — the child is very limp and exhausted. In fact, one of the hallmark characteristics is low muscle tone. When babies have small muscles and thereby trouble sucking, it makes feeding almost impossible.

“They just lie there. They look like they’re melted into the bed they’re so limp,” Clark says. “If you don’t wake up, you don’t learn and your brain doesn’t develop.”

Not only are most of these babies tube-fed, the drive to learn more is also delayed. Parents have to mimic almost all milestones, even something as simple as lifting the head. Most infants with PWS can’t sit up or roll over until they’re almost 1, far behind average children the same age.

Another characteristic of PWS patients is strange behavior which presents itself in three potential phases.

In phase one — known as hypophagia — the desire to eat does not exist, and usually lasts until the child is 2 years old. During phase two, a healthy appetite appears and children begin to seek food. Phase three is the most well-known. In this phase — known as hyperphagia — the individual is constantly hungry and never feels satisfied. In some reported cases, individuals will choke because of how quickly they consume food.

“Parents can’t have a bowl of apples on the counter,” Clark says. “They can’t even have a refrigerator that is unlocked. Everything has to be under lock and key. The kids can’t help it. They literally feel like they are starving. And if they know they can get food, their behavior becomes worse.”

Sophie is currently in the hypophagia phase of PWS. She doesn’t fuss when she is hungry and eats on a schedule. She still consumes a few bottles every day, but has progressed to eating food that an average child her age would eat.

Hungry for a cure

Currently, there is no cure for PWS, but early intervention can help ensure these children grow up to lead normal lives. A synthetic human growth hormone (HGH), used for pituitary replacement, can make a significant difference in muscle strength and growth.

In fact, it’s becoming the standard in caring for these patients, starting at just a few days old. However, giving the child HGH doesn’t fix the chromosome entirely, but rather aids the gene in what it isn’t doing correctly.

As for Sophie, the future is looking bright. Soon the family will be doctoring closer to home … in Fargo. But the journey is still an uphill battle.

“Besides her being weak, I couldn’t tell the difference between her and another baby,” Waylon says. “The only thing she is lacking is her strength right now. She isn’t crawling or walking, but she can roll like nobody’s business. That’s how she gets around.”

Sophie’s parents know they will need to create a life for her that includes plenty of activity and a strict diet to make sure she can live the best life possible.

“She is pretty close to all of her milestones,” Steph says. “It’s nice to know things get better. As things get better on this end, then it’s the hunger (phase). We just have to be prepared.”

Seeking support

A good support system, like the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association, can mean a world of difference to young parents whose child has the disease.

Social media also offers a great deal of support to parents. Facebook groups create a community for parents of children with this condition, encouraging them to ask questions, share their children’s progress and provide coping mechanisms. Facebook recipe pages and therapy toy exchanges also take place within these groups.

“If you have questions, there are people who can answer you in 30 seconds,” Steph says. “It’s all on Facebook. You can call people even. And every Friday they have a proud moment of the week for parents to share things their child has done.”

Fostering a sense of community on social media has connected parents, reminding them they’re not alone in this long journey.

By Emma Vatnsdal for inforum.com

Jennifer Bolander has been serving as a Special Education Specialist for PWSA (USA) since October of 2015. She is a graduate of John Carroll University and lives in Ohio with her husband Brad and daughters Kate (17), and Sophia (13) who was born with PWS.

Jennifer Bolander has been serving as a Special Education Specialist for PWSA (USA) since October of 2015. She is a graduate of John Carroll University and lives in Ohio with her husband Brad and daughters Kate (17), and Sophia (13) who was born with PWS. Perry A. Zirkel has written more than 1,500 publications on various aspects of school law, with an emphasis on legal issues in special education. He writes a regular column for NAESP’s Principal magazine and NASP’s Communiqué newsletter, and he did so previously for Phi Delta Kappan and Teaching Exceptional Children.

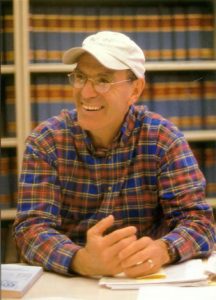

Perry A. Zirkel has written more than 1,500 publications on various aspects of school law, with an emphasis on legal issues in special education. He writes a regular column for NAESP’s Principal magazine and NASP’s Communiqué newsletter, and he did so previously for Phi Delta Kappan and Teaching Exceptional Children. Evan has worked with the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association (USA) since 2007 primarily as a Crisis Intervention and Family Support Counselor. Evans works with parents and schools to foster strong collaborative relationships and appropriate educational environments for students with PWS.

Evan has worked with the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association (USA) since 2007 primarily as a Crisis Intervention and Family Support Counselor. Evans works with parents and schools to foster strong collaborative relationships and appropriate educational environments for students with PWS. Dr. Amy McTighe is the PWS Program Manager and Inpatient Teacher at the Center for Prader-Willi Syndrome at the Children’s Institute of Pittsburgh. She graduated from Duquesne University receiving her Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Education with a focus on elementary education, special education, and language arts.

Dr. Amy McTighe is the PWS Program Manager and Inpatient Teacher at the Center for Prader-Willi Syndrome at the Children’s Institute of Pittsburgh. She graduated from Duquesne University receiving her Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Education with a focus on elementary education, special education, and language arts. Staci Zimmerman works for Prader-Willi Syndrome Association of Colorado as an Individualized Education Program (IEP) consultant. Staci collaborates with the PWS multi-disciplinary clinic at the Children’s Hospital in Denver supporting families and school districts around the United States with their child’s Individual Educational Plan.

Staci Zimmerman works for Prader-Willi Syndrome Association of Colorado as an Individualized Education Program (IEP) consultant. Staci collaborates with the PWS multi-disciplinary clinic at the Children’s Hospital in Denver supporting families and school districts around the United States with their child’s Individual Educational Plan. Founded in 2001, SDLC is a non-profit legal services organization dedicated to protecting and advancing the legal rights of people with disabilities throughout the South. It partners with the Southern Poverty Law Center, Protection and Advocacy (P&A) programs, Legal Services Corporations (LSC) and disability organizations on major, systemic disability rights issues involving the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and the federal Medicaid Act. Recently in November 2014, Jim retired.

Founded in 2001, SDLC is a non-profit legal services organization dedicated to protecting and advancing the legal rights of people with disabilities throughout the South. It partners with the Southern Poverty Law Center, Protection and Advocacy (P&A) programs, Legal Services Corporations (LSC) and disability organizations on major, systemic disability rights issues involving the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and the federal Medicaid Act. Recently in November 2014, Jim retired.